In honour of Black History Month 2023, Your Students’ Association Advice Service Coordinator Elena Semple shares their journey from feeling like an outsider, to embracing their multifaceted identity.

Growing up, I was always the ‘coconut’ among my friends and acquaintances. This designation did not arise from an idiosyncratic fondness for coconuts; it was because of my skin colour. I had brown skin on the outside, but they considered me ‘white’ on the inside. The term ‘coconut’ is often used to describe someone with dark skin who supposedly acts or thinks like they are white, as if skin colour should dictate one’s personality or identity. This label haunted me for years, but eventually, I learned to embrace my identity beyond my skin colour. From my early days in the United States to my experiences in Scotland, various personal challenges and revelations have shaped my understanding of identity.

My mother and I immigrated to the United States from Bolivia in the 1990s when I was merely two years old. Our move was motivated, in part, by the pursuit of political asylum, as we joined other family members already settled in the US. My mother, an unmarried parent in a less accepting era, sought new opportunities in a foreign land. Growing up in the US, I saw that my home was a rich tapestry of traditions, languages, and cuisines, as my Bolivian family was deeply rooted in our country’s customs around food, music, and beliefs. However, once I left the front door, society tried to instil in me that I had to leave that all behind and if I wanted to survive, I had to assimilate into my surroundings. It is crucial to note that my family and I lived as undocumented immigrants, necessitating constant vigilance for fear of deportation. I grew up in the suburbs, so the town’s population was approximately 95% white, so assimilation wasn’t merely about fitting in but a means of averting suspicion.

In school, I quickly realised that I didn’t fit neatly into the predefined boxes of identity that society had created. My interests, tastes, and values didn’t always align with what was expected of someone with my skin colour. I cherished Bolivian folkloric music as ardently as I enjoyed mainstream pop. I was equally comfortable conversing in my native Spanish as in English. I relished the delicious spicy dishes my mother and grandmother cooked at home and enjoyed a pepperoni pizza with friends.

Despite my multicultural upbringing, my peers and classmates struggled to fathom the possibility of embracing and embodying multiple cultural identities. It was as if I were compelled to select one facet of my heritage and adhere to it exclusively. This misunderstanding led to the ‘coconut’ label being attached to me, and I began feeling like an outsider in my community. Over time, I started questioning why skin colour had to dictate so much about who I was supposed to be. It became evident that the time had come to reject this stereotype and embrace the authenticity of my multifaceted identity, forged through my unique experiences, choices, and values.

Towards the end of high school, I grew increasingly vocal about issues impacting immigrants in the United States. I even composed a letter to a State Senator, boldly expressing my solidarity with immigrant strikes and actions during the early 2000s. I must admit that sleep eluded me for weeks, weighed down by the fear that I had inadvertently exposed myself and my family to potential repercussions from Immigration Control Enforcement. To my astonishment, the Senator responded, commending my courage and gratitude for speaking out. This marked my initial foray into activism, a memory I revisit during uncertain times.

As I entered university in 2007, I carried the lessons of my high school activism. When I moved to Scotland to attend university, I gradually realised that I could unapologetically represent my cultural heritage and draw strength from the myriad influences that had shaped me. Nevertheless, being identified as Latinx held limited significance in Glasgow during that period, as the Latinx community was notably small. People’s understanding of my culture was primarily informed by what they had gleaned from Mexican culture or their experiences during Spanish holidays. Once again, I found myself being categorised as ‘American’ before anything else, and many individuals expressed surprise at my ‘white voice.’ My awareness of this stemmed from my experiences working in call centres, where people often expressed relief at speaking to someone they perceived as ‘white’ rather than ‘foreign.’ In the hospitality industry, managers often delivered instructions loudly and slowly, presuming that I did not possess proficiency in English until I spoke. However, once my American identity became evident, their demeanour would shift. It became apparent that among workers of colour, the American white-passing accent was accorded a peculiar favour.

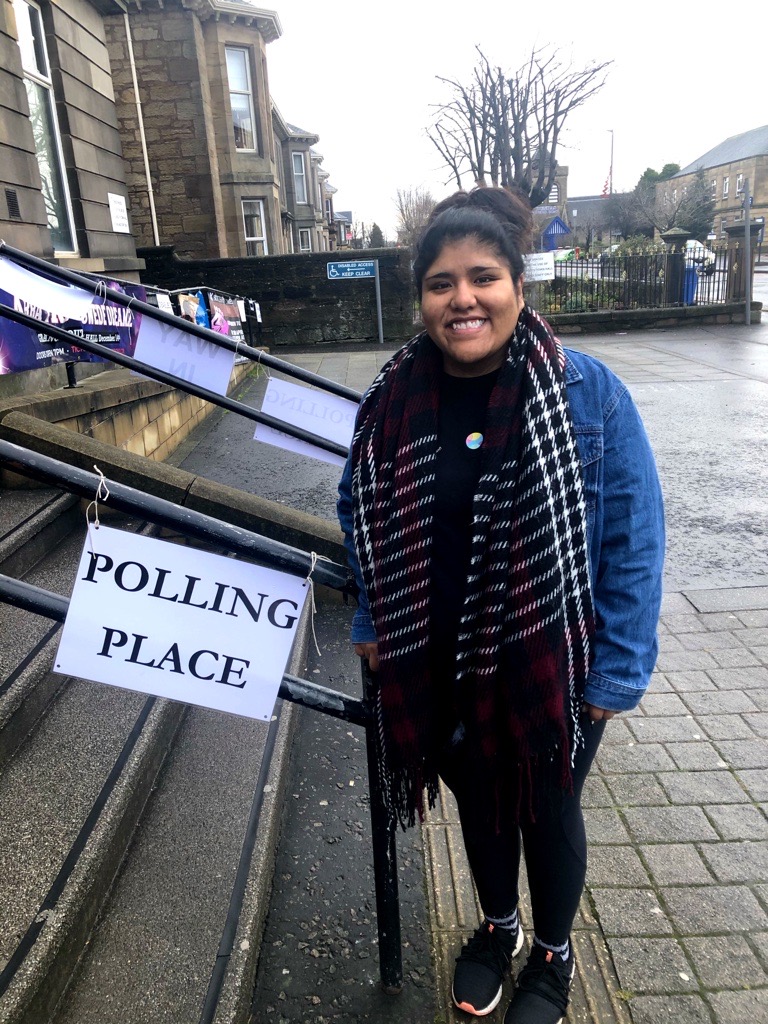

It’s 2023, and the concepts of inclusivity and equality are prominent in our collective consciousness. While Scotland has made considerable progress, there remains work to be done in fostering an inclusive society. Fortunately, university spaces offer places for students to learn from other cultures and appreciate the richness we bring and want to contribute to society. My journey towards embracing my heritage reached a pivotal juncture in 2017 when I became actively involved in the student movement. This period marked a profound shift in my perspective concerning the term ‘coconut.’ Rather than perceiving it negatively, I began to view it as a testament to my unique capacity to bridge disparate worlds and wholeheartedly celebrate the beauty of diversity.

As I delved deeper into the student movement, I encountered kindred spirits who, like me, defied society’s narrow definitions of identity. We formed a close-knit community that revelled in our diverse backgrounds and cherished the freedom to be our authentic selves. As I grappled with the intricate puzzle of race, my other facets of identity, including my sexual orientation and neurodivergence, began to merge; I gained a profound appreciation for the concept of intersectionality. Collaborating with fellow students during my tenure at the NUS, we pushed back against stereotypes. We demonstrated that identity is a complex tapestry woven from a multitude of experiences and influences.

Today, I no longer cringe at being called a ‘coconut’. It no longer suggests that an inner layer is better than the outer layer. Instead, I wear it as a badge of honour, a reminder of my capacity to defy stereotypes and carve out my identity. This reimagined interpretation underscores the value of the coconut’s external and internal facets, emphasising the importance of embracing the entirety of one’s identity rather than privileging one perspective over another. I’ve learned that being true to oneself is more important than conforming to others’ expectations. My journey has reinforced the idea that our worth is not predicated on the colour of our skin but on the depth of our experiences, the complexity of our character, and the authenticity of our hearts.

Your Students’ Association offers UHI students the opportunity to join Student Networks that provide a nurturing environment where individuals with diverse backgrounds and interests can come together to celebrate their unique identities and experiences. They offer a safe space for students to explore their passions, values, and cultural heritage. Click here to find out what networks are available.